2019 Dhaka – Special Economic Zones: Why is it timely to have a fresh look at the concept and how?

The first round in United States (U.S.)-China trade war is almost over. Yet, it looks highly plausible that that the contest for leading trade will not end here. The process of relocation of U.S. Global Value Chains (GVCs) to different countries will continue. The disruption this development will bring to existing GVCs will not only bring with it risks, but also opportunities to the Asia-Pacific region as well as the Confederation of Asia-Pacific Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CACCI) member states. This is especially important since the CACCI member states (1) comprise 37.9 percent of the world population whilst only accounting for 25.6 percent of all exports and receiving 19.8 percent of the global income. (2) Hence, taking a constructive stance, it is of interest to CACCI member states to take advantage of GVCs-related opportunities.

In detail, issues and opportunities that could arise from relocating certain GVCs out of China has already been put under the microscope. The debate has, predominantly, been fueled by the rising income levels as well as the on-going transformation of China from labor-intensive manufacturing to more sophisticated manufacturing processes. Hence, while China’s transformation is spearheading the country’s improvement in its production processes and product sophistication levels, China is losing its comparative advantage of being an inexpensive country for production of goods. This reality, in turn, offers an unmissable opportunity for CACCI members to become a part of global production lines.

To expand, while this opportunity area (i.e. increased wages) was expected to take place in the near future, there is consensus as to the role of trade wars and China’s advancements in production capabilities in expediting the need to shift GVCs from China to other countries. It is of importance to also mention that the process of shift mentioned is expected to accelerate even more in the near future due to the expected second round of the trade wars. In relation, countries in the vicinity of China, or countries that have the highest chance of being to country of destination with regards to GVCs relocation, have to swiftly create a comparatively more conducive business environment to, primarily, attract these GVCs and also help them flourish. In short, interested countries must become ready.

This can only be achieved with an in-depth analysis of what entices GVCs to choose and relocate to certain countries over others. Referring to the example of China, a criterion is evidently identified and also proven, cheap labor (therefore production). It is important to note, however, analysis pertaining to the development and sustainability of GVCs assert that there are other factors that come into play aside from comparatively lower wages in order to prompt a shift in GVCs from a country to another. (3)

This begs the question; Why the need for a fresh look at an old concept like SEZs in this position paper? Three reasons4 are especially important.

Primarily, and as mentioned before, GVCs have already started looking for opportunities to relocate out of China due to rising wages. This search by GVCs, up until recently, lacked a politically motivated pull factor. In the regard, U.S. – China trade wars and the developments surrounding this race offers just that; an environment in which countries, especially those in the vicinity of China, will be able to increase their existing demand to beyond that of their natural absorption capacities. Hence, the need for more actively managed mechanisms to make the shift of GVCs from China to other countries in the region possible.

Secondly, as also noted in the ADBI-OECD report, the presence of cheap labor has become insufficient to explain GVCs’ reasons to choose certain countries over others. To elaborate, a key finding in the study of GVCs “…is that GVCs do not respond to piecemeal approaches to policy change” and that a “…’whole of the value chain’ approach is needed.” (OECD5, 2017). Evidently, this approach is defined, to an extent, by policies that are horizontal such as having good infrastructure, high connectivity and efficient logistical network, good rankings in Doing Business (and other similar indexes), flexible labor markets and doing investments in human capital through education and training. These horizontal policies are supported by targeted policies determined in accordance with what the country is seeking to achieve. Targeted policies include removal or modulation of trade and investment restrictions, discriminatory subsidies and incentives, local-content stipulations and restraints on foreign exchange (Ibid). In other words, there are numerous policy and practice level actions that entice GVCs, and that need to be taken by the country interested to become a part of the GVCs.

Specifically, issues pertaining to levels of connectivity, having efficiency logistics infrastructure and network, and having an inducive regulatory environment are especially important and the ADB report underlines that most countries in the run for becoming a hub for GVCs lose out on these fronts.

Thirdly, Small Medium Enterprise (SME) dominated private sector in CACCI countries necessitate a distinct type of operation interface than that of the Chinese. To elaborate, this distinct operation interface must primarily be member state specific, therefore considerate of its business environment. Subsequently, the interface in question have to collect procurement contracts and mobilize SMEs to manufacture by way of providing credit, logistical support and guaranteed standards of services to fulfill the contract conditions to the best of these SMEs’ ability.

Taking all the information provided above into consideration, this CACCI Position Paper offers the establishment of new and improved Special Economic Zones (SEZs) with distinct governance structures and regulatory framework that are considerate of global trends, in respective CACCI member countries. The underlying goal of these Zones will be to attract GVCs through the creation of conducive, highly-regulated business environments. In other words, SEZs offer controlled environments where newly introduced policies and practices are comparatively more likely to yield expected outcomes.

Keeping these in mind, what are SEZs? These Zones are geographically defined areas that are generally administered by a single body. Specifically, these offer conducive incentives (i.e. more liberal and simplified economic regulations) for businesses to establish their locations in the Zone and operate. Traditionally, SEZs are established and operated as part of national economic development reform strategies in respective countries, and range in size and scope, from individual small industrial parks to entire regions of a country. Moreover, SEZs are zones where good practices of regulatory framework are carried-out, simplified procedures for establishing and operating enterprises are followed and certain tax advantages are offered. Importantly, SEZs offer a stable and effective business environment allowing for the effective use of labor while also showing commitment to environmental standards.

Differing from the explanation of SEZs above, the new and improved SEZs will specifically serve the GVCs. Hence, Chambers are provided with a great opportunity in which they can play an important and active role in the establishment of pilot SEZs using their global networks, sectoral and value-chain know-how and previous experiences in establishing and operating Zones of similar stature. Furthermore, these SEZs would be designed in consideration of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and established accordingly.

In line with this, with regards to Turkey and its region, this new interface (SEZs 2.0) in question will have to consider a situation unique to our region: The 5.6 forcibly displaced Syrians in neighboring countries. As the mark of a decade into Syrians’ forced displacement is fast approaching, the protracted nature of forced displacement requires stepping out of the initial humanitarian response to a sustainable, long-term approach based on encouraging self-resilience and inclusiveness. This begs the question; how would this transition link the economies of hosting countries with GVCs? The answer lies in the migration-development nexus, which must be considerate of the economic profile and the existing policies on migration in the host country. One example is the EU-Jordan Compact. (6)

One of the raison d’etre of the Compact is to support the growth of Jordanian economy while also ensuring the self-resilience of Syrians. Therefore, the European Union (EU) committed to opening its market for Jordanian products manufactured in 18 designated economic and industrial zones. The agreement will last for 10 years (2016-2026) and the products covered under the agreement include, but not limited to, electrical and electronic products, chemical products, furniture, and cosmetics. Furthermore, the EU during the 10 year period will relax the Rules of Origin (ROO) to support Jordanian exports. The trade-off, however, is for Jordanian companies operating in the designated economic and industrial zones to formally hire a total of 200,000 Syrians.

The employment of Syrians was planned to follow a gradual increase based on yearly quotas: At least 15 percent of the workforce in any given company operating in the designated economic and industrial zones should be composed of Syrians during the first two years of the agreement. The quota then to be raised to at least 25 percent in the third year.7 The agreement, however, did not reach its full potential. A year after the agreement, only 7 out of 936 Jordanian companies in the 18 designated economic and industrial zones had obtained the necessary paperwork to become eligible to export to the EU market. Yet, not even one company out of the 7 exported even a single container that year. The primary reason for this shortcoming has its roots in the difficulty of Jordanian manufacturers to meet the EU quality standards.

Other reasons include thelack of awareness about the Jordanian product in theEU market, andthe unattractivenessofthe EU market to someJordanianmanufacturers. (8)

Presently, three years into the agreement, 13companieshave succeeded in navigating the bureaucracy to obtain the necessary documents for exporting to the EU and 6 of them began their export operations. This increase in the number of companies is the result of amending three conditions. Primarily, the EU extended the period for relaxed ROO until 2030.Secondly, the EU lowered the requirement of hiring Syrians from 200,000 to 60,000 formal job opportunities created in various economic sectors across Jordan. (9) Once achieved, the aforementioned 15 percent quota will be dropped. Thirdly, all factories in Jordan and not only the ones in the 18 designated economic and industrial zones and areas have become eligible to benefit from the relaxed ROO.

The Compact envisioned to link Jordanian products with GVCs. Establishing the link, nonetheless, faced a number of obstacles, two of which hasto do with connectivity.

Primarily, Jordan doesnot overlook the Mediterranean. Thus, reaching the EUmarket means shipping containers through the soleJordanian port located in the Gulf of Aqaba. Drawing attention to the distance from the port to the EU market and the constantly changing regulations governing customs and export tariffs, Jordanian manufacturers cannot fully benefit from the Compact. Alternative routes to exporting from Gulf of Aqaba are either shipping containers from Israel through the West Bank or Syria–both routes are subjectto political instability. Second reason, on the other hand, is Jordan’s poor transportation infrastructure. This reality, in turn, demotivated Syrians from taking jobs in the designated economic and industrial zones, resulting in the aforementioned demand of Jordanian manufacturers to lower the required number of hired Syrians. (10)

Drawing attention to the needs of growing economies, specifically in the Indo-Pacific region but relevant for all CACCI members, United States Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross asserted in the Official Mission Statement leading up to Indo-Pacific Business Forum that “…strong continual economic growth” brings with it “…an associated need for new and upgraded infrastructure”. (11) This infrastructural need is evermore present with regards to low rates of connectivity among CACCI members.

Hence, it is of this Position Paper’s view that the best way to overcome this impasse is to focus, primarily, on improving connectivity among CACCI countries, and then connectivity between us and the developed countries. This focus brings with it the apparent need to focus on the planning, development and establishment of necessary infrastructure. In this regard, SEZs 2.0 provide an opportunity, as they offer collective and easy-fix solutions to the deficiencies in infrastructure as well as regulations in the CACCI member states.

With regards to CACCI countries, the Chinese model is irrelevant because it utilizes the behemoth of companies that it has under its finger. However, this is hardly applicable to CACCI countries. Hence, positioning the matchmaking of SMEs with Multinational Corporations (MNCs) as a priority, and an essentiality for findings success in attracting GVCs to these countries has to be one of the first action to be taken.

Having said that, CACCI countries, which are predominantly SME-based economies, do already have presence in GVCs. Yet, their participation in GVCs is very limited and not reflective of their potential.

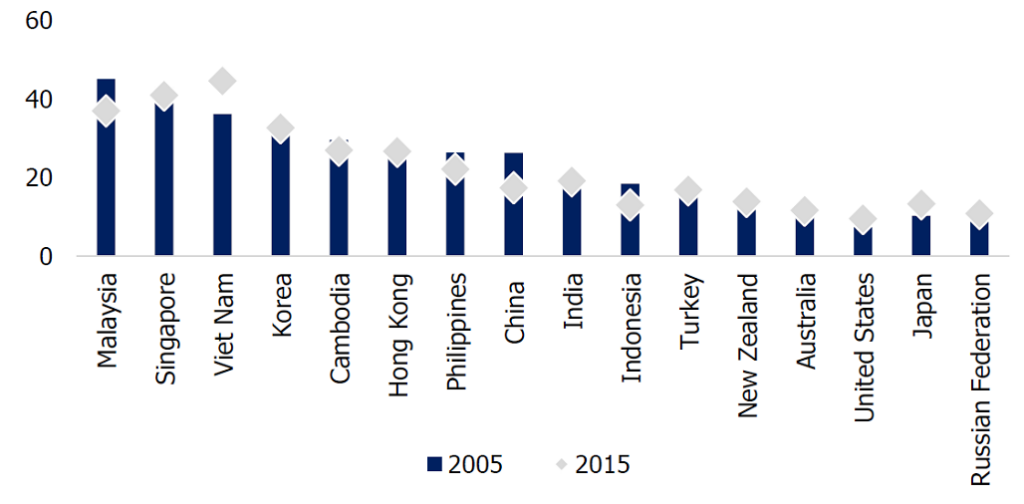

Specifically looking at CACCI member countries’ backward participation in GVCs, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam come to the fore as countries with comparatively higher import input in their exports (Figure 1). Interestingly, among the CACCI member countries, Russia and Japan come to the fore with better performances in backward GVC participation even when compared with the U.S. Whilst, Russia’s position can be explained through its role as one of the largest exporters of natural gas and oil, Japan shines as a country with a relatively good performance in its backward link to GVCs.

Figure 1. Backward participation in GVCs, foreign value-added share of gross exports, by value added origin country, CACCI member countries, U.S., and China, %, 2005-2015

Note: CACCI member countries except for Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, Mongolia, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan.

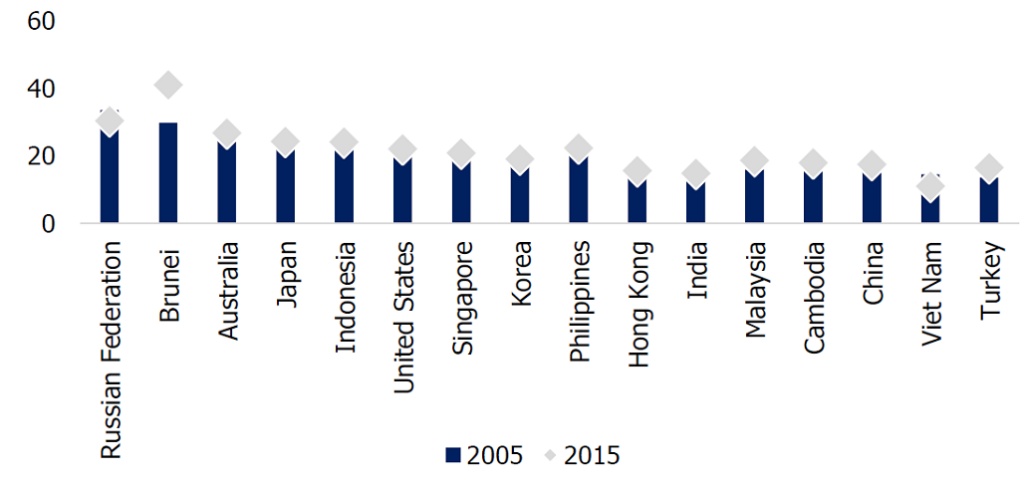

On the other hand, with regards to CACCI member countries’ forward participation in the GVCs, Turkey comes to the fore as the country with unsatisfactory forward participation in GVCs, followed by Vietnam, Cambodia and Malaysia. Interestingly, Russia, once again, takes the lead but this time in forward participation to GVCs. Russia is trailed by Brunei, Australia, Japan, and Indonesia.

Figure 2. Forward participation in GVCs, domestic value-added in foreign exports as a share of gross exports, by foreign exporting country, CACCI member countries, U.S., and China, %, 2005-2015

Source: OECD, TEPAV visualization

Note: CACCI member countries except for Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, Mongolia, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan.

Looking at the Figures above, it is important to note that there lies an opportunity. Yet, the identification of areas, products or sectors that show the greatest potential for commercial relations among the CACCI countries but also with regards to GVCs require further and in-depth analysis.

All in all, CACCI countries, even thouh mostly non-reflective of their potential, have presence, both, in backward and forward participation in GVCs. With new developments with regards to GVCs and China unfolding, opportunity for CACCI member countries to get closer to reaching their potential is up-for-grabs, This Position Paper views that SEZs offer the shortest and paciest route to getting there.

Special economic zones have been around to achieve specific objectives. Three can be useful for our analysis:

Firstly, SEZs are there to provide public services at an excellent level to both foreign and domestic investors. As the government cannot do this all through the country due to problems with infrastructure, it tends to do this in a piece of land designated for investments.

Secondly, the government may choose to provide a group of select investors a preferential regulatory environment that is different from other national schemes. For example, the Chinese SEZs were developed out of the need to diversify.

Thirdly, SEZs might be positioned as a designated space to attract specific investors where migratory movements can be utilized to the betterment of economy. In order to integrate migrants to host country labor markets, humanitarian aid may take the form of providing procurement contracts to firms which are partially employing migrants, provided that a conducive environment like no child labor is guaranteed. Specific to the last point, SEZs are controlled environments in which these kinds of guarantees can be given and followed through.

To contextualize the role of SEZs, The Jordan Compact cannot be dismissed as an unqualified success. Revisiting the old concept of SEZs in a new manner should extract lessons learned from the Compact experiment. Thus, three more features can make the new interface of SEZs more successful.

First, SEZs need to be privately and actively managed. One positive trait of developers and managers of SEZs being from the private sector is the expedited navigation of bureaucracy through one-stop shop services in SEZs. This swiftness will be positioned to act as an incentive for investors to offer decent work to immigrants, resembling a ‘carrot and stick approach’. For example, the Zone’s operator company could become responsible of handling the work permits of immigrants and refugees. Moreover, remaining eligible for operating the SEZs will be tied to the operator company fulfilling the set targets on (i.e. number of work permits).

In addition, operator companies will also be responsible of securing procurement contracts for SMEs operating in SEZs. This involvement will be a cornerstone to setting the initial link to GVCs.

Lastly, the success of the new interface greatly rests on the governance of structure of SEZs.(12) In addition to the Jordan Compact, other examples must be identified and analyzed so as to devise a governance structure that best suits the business environment of the country in question. More importantly, the governance structure should be designed in such a way that it not only is considerate of the business environment but also aims at maximum utilization of immigrants’ skills-set.

In that note, it is important to mention that the structure of the Jordan Compact is being replicated in an African country: Ethiopia. The idea behind the Ethiopian Jobs Compact is to link the financial support to the government of Ethiopia’s industrialization strategy with a transition from out of camp policy by opening the labor market access for refugees. The pledged financial support package foreseeing the creation of more than 100,000 jobs of which 30,000 will be allocated for refugees. (13)

There are, however, similarities and differences between the two Compacts.Both Compacts aim to link export-oriented manufacturing businesses with GVCs. Unlike the Jordan Compact, however, the Ethiopian Compactdoes not specifically mention the EU market as the solo export destination. Furthermore, the Ethiopian Compact pledges to increase school enrollment for refugees in primary, secondary, and tertiary education. Another pledge, for example, is the issuance ofbirth certificates for refugee children born in Ethiopia. (14) Thus, there cannot be exact replicas of compacts and the components must include the socio-economic policies of the hosting country. Nevertheless, it seems that local integration policies of refugees could be subject to progress in establishing linkages with GVCs.

- CACCI can establish a Trade Facilitation Center aimed at information dissemination and capacity-building forCACCI member countries.

- CACCI can take an active role in becoming the operator company for the SEZs.

- CACCI can play a pioneering role in carrying-out research activities to assess the optimal ways in which intra-CACCI connectivity can be established, border-crossings can be modernized, and regulations and standards can be streamlined.

- CACCI can play a pioneering role in establishing an internet-based SME market and help with developing CACCI-memberstate specific e-trade schemes.

- CACCI can play a pioneering role in identifying the skills-set of immigrants that could potentially be employed in the SEZs established byCACCIcountries so as to optimize skills and job matching.

It’s like the saying goes: “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is now.”

Unlike twenty-years ago, presently CACCI members are faced with an opportunity that needs to be seized which would ensure their economic growth and prosperity in the long run. This opportunity, as outlined in this Position Paper, stems from China’s changing production structure as well as its contest to replace the U.S. as the decision-maker in trade agreements. Combined with these, the MNCs’ willingness to relocate their value chains to other countries, preferably in the same region, have made this opportunity a reality.

Going forward, CACCI members would benefit the most from striving to increase their presence and share in GVCs. Yet, relocation of GVCs, or better yet, a country’s attractiveness for this relocation has more to do than having cheap labor in the destination country. Aside from cheap production capabilities, research shows that the potential destination country for GVC relocation needs to provide both horizontal and targeted policies so as to become an enticing option.

As a response to these expectations, this Position Paper asserts that SEZs offer the best possible way of finding success in all lanes and in a comparatively shorter time. As important, these SEZs have the potential to be attuned to the targets set in SDGs, hence becoming even more attractive to 21st century phenomenon that is the ‘conscious consumer’ while also providing employment opportunity to not only to locals but to the immigrant population as well. In this regard, Jordan Compact and Ethiopian Jobs Compact, as specified above, can offer to examples as to how a framework for a similar undertaking can be devised for CACCI member states.

As it stands, CACCI can play an active role in promoting, both among its members and globally, the role SEZs can play if correctly positioned within GVCs. By this way, CACCI would not only allow for improved economic conditions in its member states by paving the way for them to reach their potential, but also would set a global example that adheres to human rights and development goals.

Footnotes:

(1) There are currently 30 Primary Members from 28 countries or independent economies around the region.

(2) World Bank, UN Comtrade, CEPII BACI, TEPAV calculations.

(3) Global Value Chain Development Report, 2017, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

(4) Special Economic Zones: Progress, Emerging Challenges, and Future Directions, 2011, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank.

(5) Inclusive Global Value Chains, 8 April 2017. OECD.

(6) EU – Jordan Partnership: The Compact, March 2017, European Commission.

(7) Relaxed Rule of Origin between Jordan and the European Union, 2016, Jordanian Ministry of Industry and Trade.

(8) Local factories didn’t benefit from Relaxed Rules of Origin,” 28 February 2017. Alwakaai.

(9) The government announces a plan to increase exports to Europe.” 7 July 2019. Alghad.

(10) Examining Barriers to Workforce Inclusion of Syrian Refugees in Jordan”. July 2017. BetterWork.

(11) Indopacific Mission Statement 2019, 20 September 2019, The U.S. Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration, export.gov

(12) “Forced migrants: labor market Integration and Entrepreneurship”, 22 May 2018. Sak, Guven. Kaymaz, Timur. Kadkoy, Omar. Kenanoglu, Murat. Forced migrants: labor market Integration and Entrepreneurship.

(13) “Jobs Compact Ethiopia”. 24 June 2019, UK Departmentof International Development.

(14) “International Development Association Program Appraisal Document”, 4 June 2018, WorldBank.