2014 Trade Liberalisation and Facilitation

In a world of increasing global trade, products are no longer made in one place with input from one country alone. Manufacturers look to reduce costs and seek component supply from many locations according to price and convenience, in order to produce a good at lowest cost and compete for consumer attention.

In an ideal world, the World Trade Organisation rules and multilateral agreements on global trading frameworks that reduce inefficiencies would prevail, however with the difficulties in finalizing the Doha Round, nations are increasingly turning to bilateral and regional trade agreements to secure advances in competitive supply chains with their major trading partners.

Again, in an ideal world these “smaller” trade deals would be aimed at WTO compliance with an eventual goal of seeing them all linked together under the WTO. To this end, the more similar the trade deals, the more trade facilitating they will be.

In the end, free trade agreements are designed to improve international trade and ultimately reduce costs for consumers. The commercial business interest is to be able to access and comply with the terms of each agreement in an efficient way. To this end, standardisation across international trade is trade facilitating. If producers and manufactures know that by doing something the same way each time they develop a product, then they can predict the requirements with certainty. This means the process can be repeated and then automated, which reduces costs for repetitive processes.

The costs of border crossing can be a sizable component of the final built up costs to production costs for manufactures and ultimately end consumers. Producers need to be aware of all of the rules and systems for each market. Complex market entry requirements mean that companies need to have staff or advisers analysing the entry systems, and then internal staff at each level of the transaction process must understand these requirements so they can take advantage of the entry requirements. Business costs are reduced when these systems are predictable and repeatable.

In the increasingly complex world of international trade, with goods passing through many hands before the final consumer, the traceability of the origin of the goods is increasingly important. The systems to support the statements that importers and exporters require for market entry and for specific rules relating to preferential trade agreements need to be streamlined and harmonised to reduce costs and complexity to business. Harmonisation around commonly used systems reduces costs and the best of these systems are harmonised and already well accepted by business outside of the FTA’s. By co-opting the most commonly-used practices already employed by business, rules of origin under FTA’s will be less costly and more efficient.

The ASEAN Business Advisory Committee (ASEAN BAC) along with the Asian Development Bank and a number of independent studies have indicated that despite widespread Government interest in free trade agreements, utilisation by commercial companies is low.1 There may be a number of reasons for this but awareness of the agreement features if often one reason for low use, but similarly difficulty in accessing the benefits is also cited as a reason for low participation.

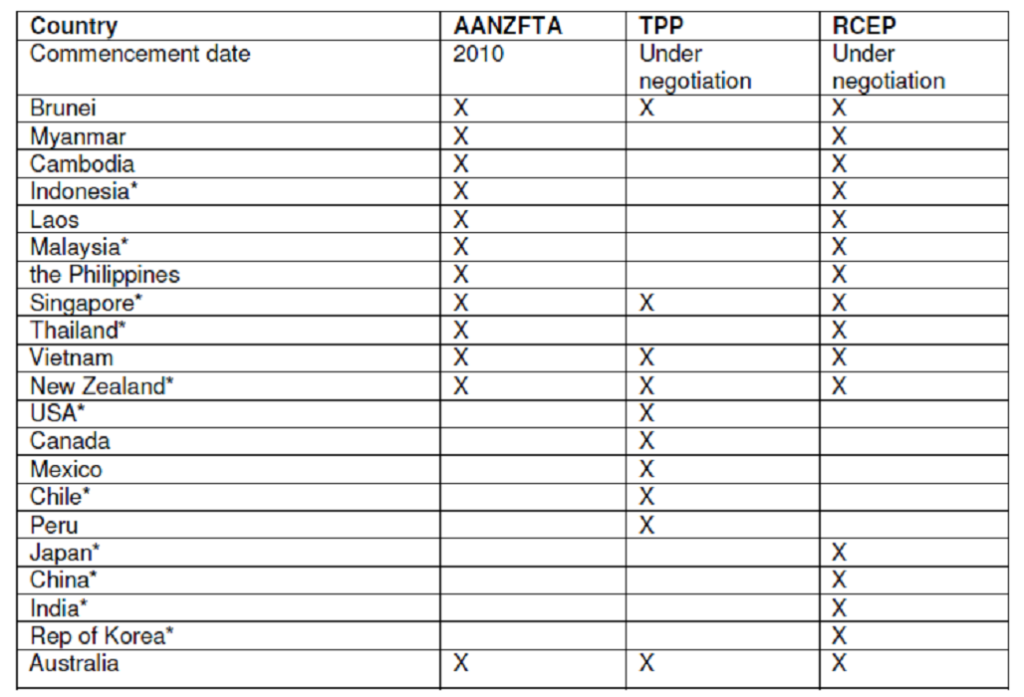

Given that Australia and many Asian nations are now party to two other regional Free trade agreements in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and now the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which both involve largely the same group of Asian trading partners, we are concerned that instead of a predictable harmonised system for trade and investment, each agreement could result in differing approaches covering largely the same markets, (at odds with the pre agreement systems) thus impacting negatively on business costs and reducing progress towards Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedures.2

CACCI needs to encourage and support Government efforts in trade liberalisation and facilitation but we, as collective Chambers of Commerce across our region also need to take a leading position to inform Governments of the needs of business and the common processes available through Chambers that can assist to improve trade within global supply chains.

In December 2013, WTO members reached consensus on the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) at the Ministerial Conference held in Bali, Indonesia.

The TFA contains twelve articles regarding Trade Facilitation and Customs Cooperation in Section I, ten articles on special and differential treatment for developing countries and least-developed countries in Section II and two articles on institutional arrangements and final provisions in Section III. The TFA deals almost entirely with Customs-related topics.

Section I

Art.1 Publication and availability of information

Art.2 Consultation

Art.3 Advance ruling

Art.4 Appeal/Review procedures

Art.5 Other measures for transparency etc.

Art.6 Fee and Charges

Art.7 Release and Clearance of goods

Art.8 Border Agency Cooperation

Art.9 Movement of goods intended for import

Art.10 Formalities

Art.11 Transit

Art.12 Customs cooperation

Section II

Special and Differential Treatment for Developing Countries and Least-Developed Countries

- Rules about Categories A, B and C

- Assistance for Capacity Building

- Information to be submitted to the TF Committee

- Final provision

Section III

Institutional arrangements and final provisions

- Committee on Trade Facilitation

- National Committee on Trade Facilitation

- Final provisions

Unfortunately recent WTO sessions failed to secure the adoption of the protocol on the Trade Facilitation Agreement.4

Irrespective of WTO developments, the World Customs Organisation has developed an online toolkit of information to assist parties to implement the “Bali package”.5

In the absence of progress in the WTO, the Governments across the region have negotiated a number of bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements in pursuit of improved trade and investment opportunities which seek to benefit the national and regional economy, our national political interests and importantly our commercial sector.

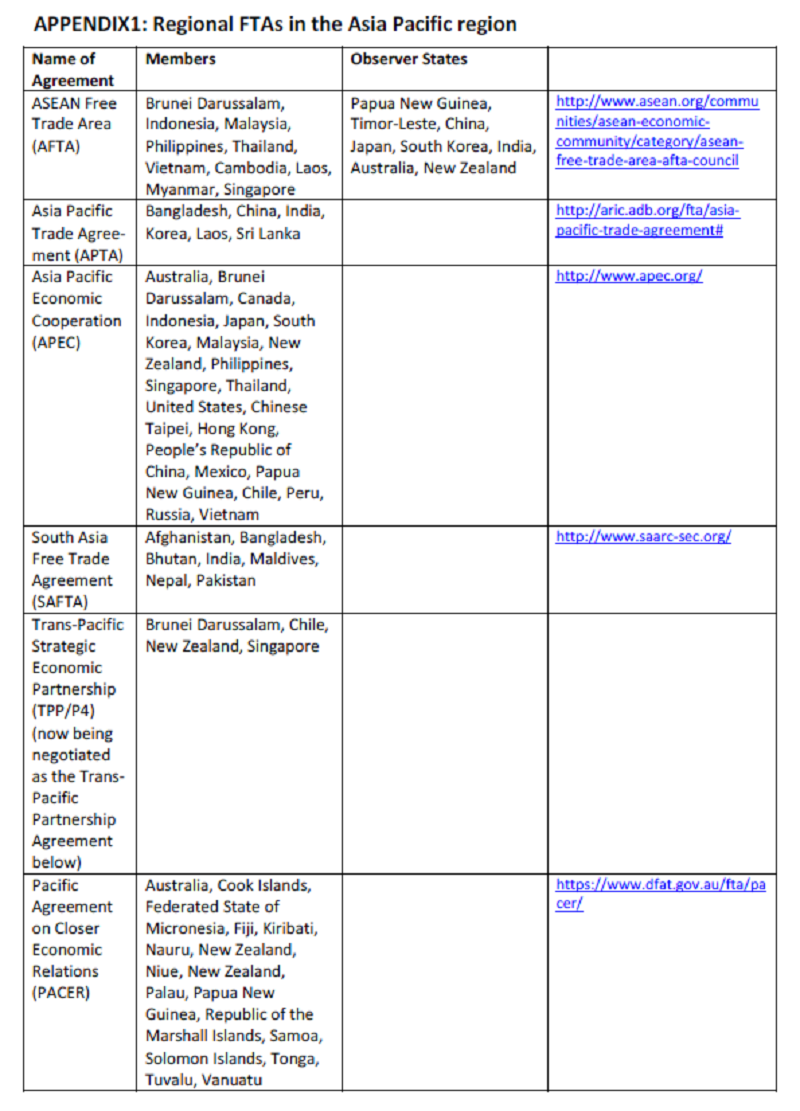

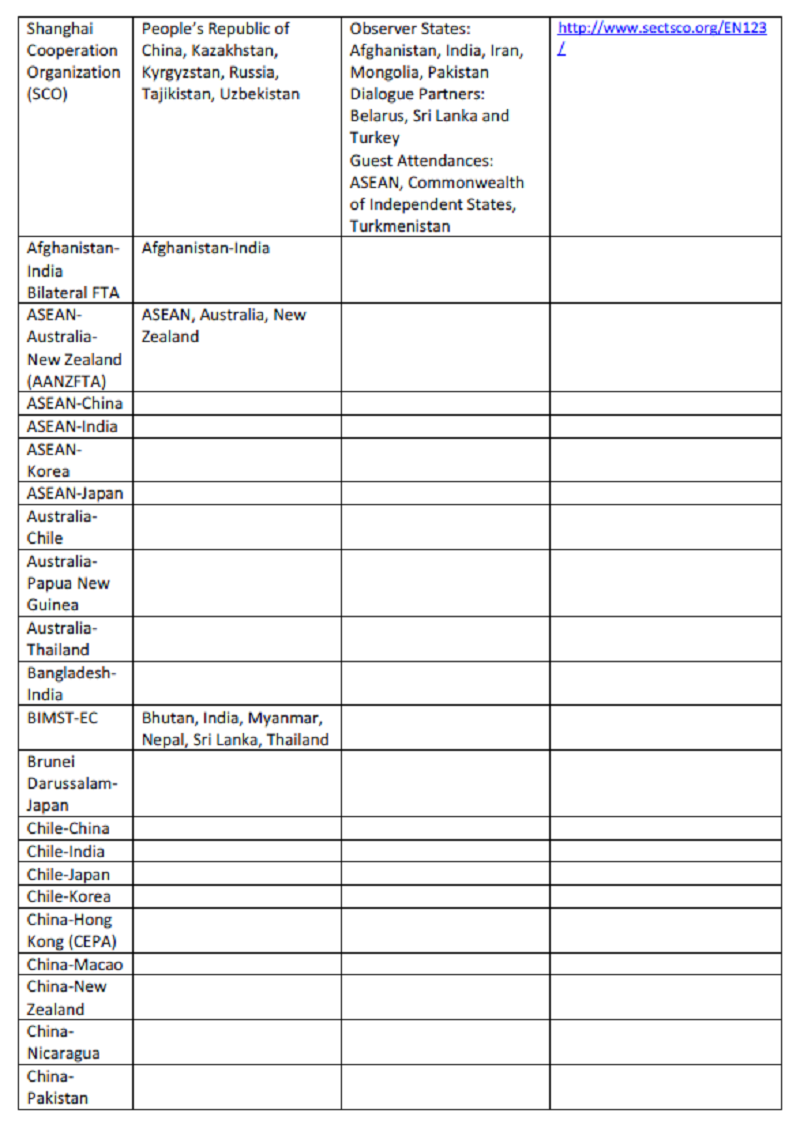

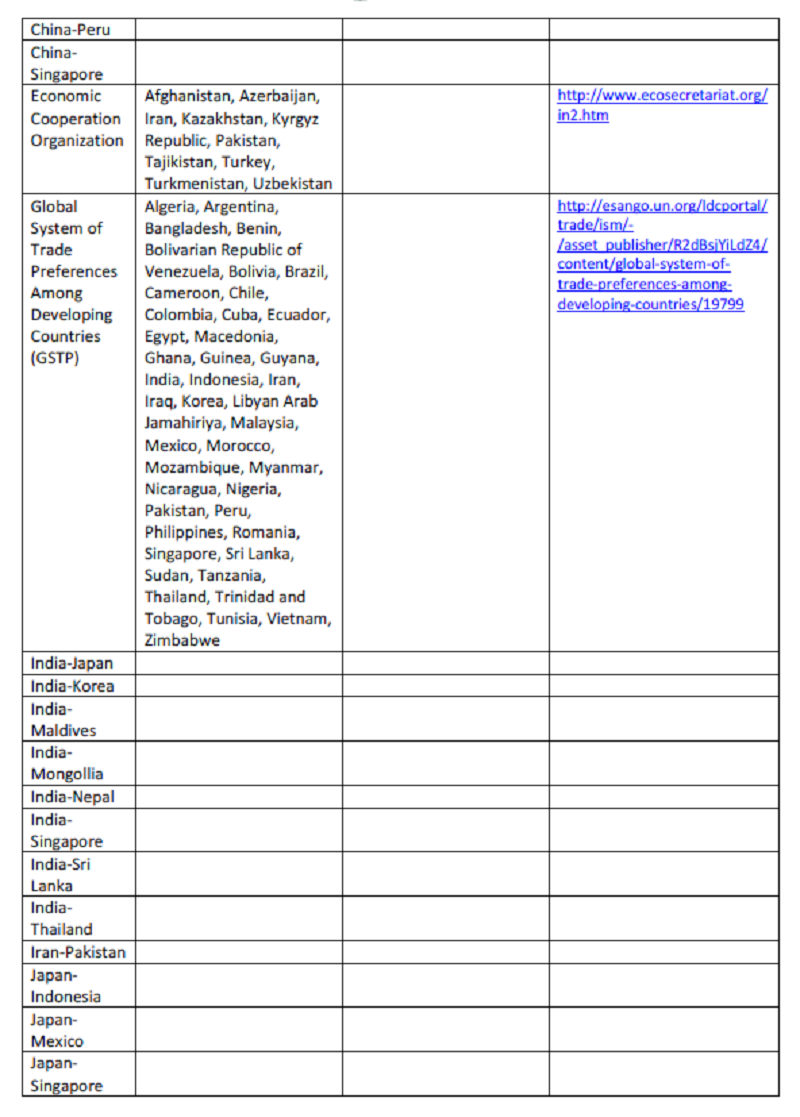

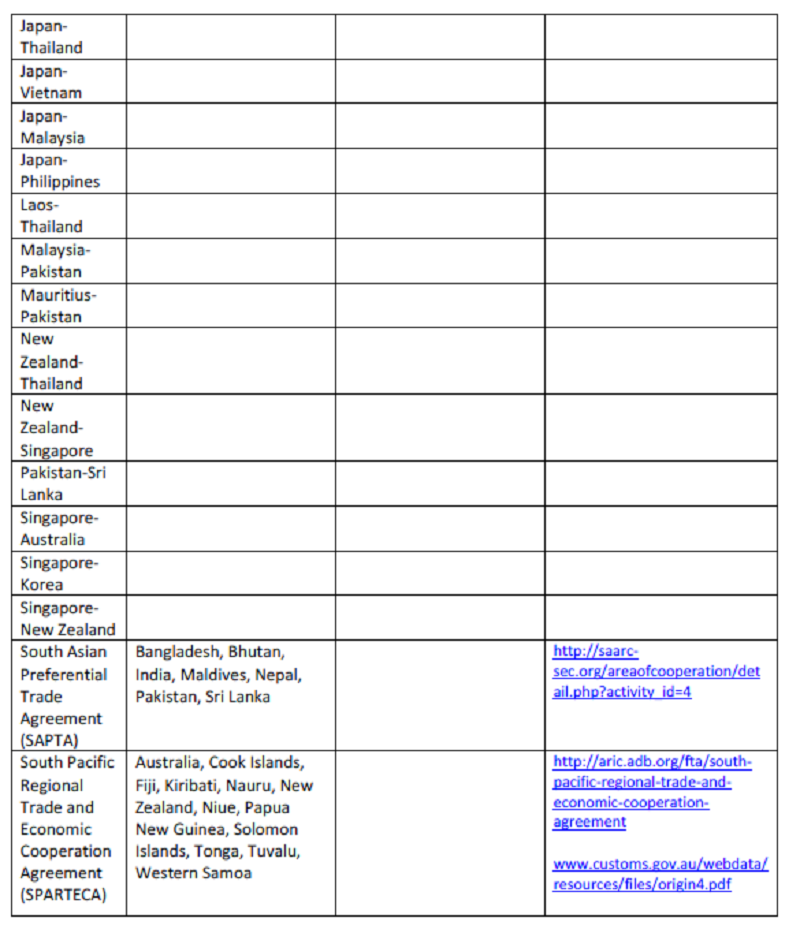

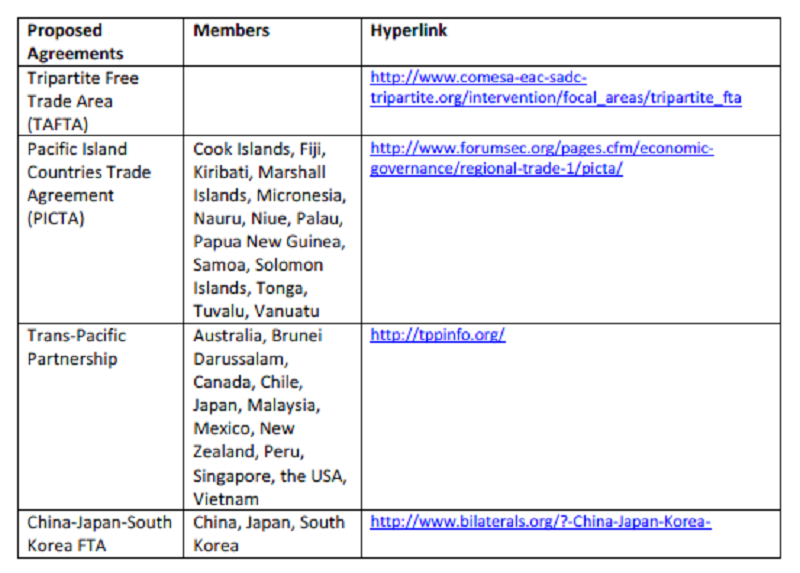

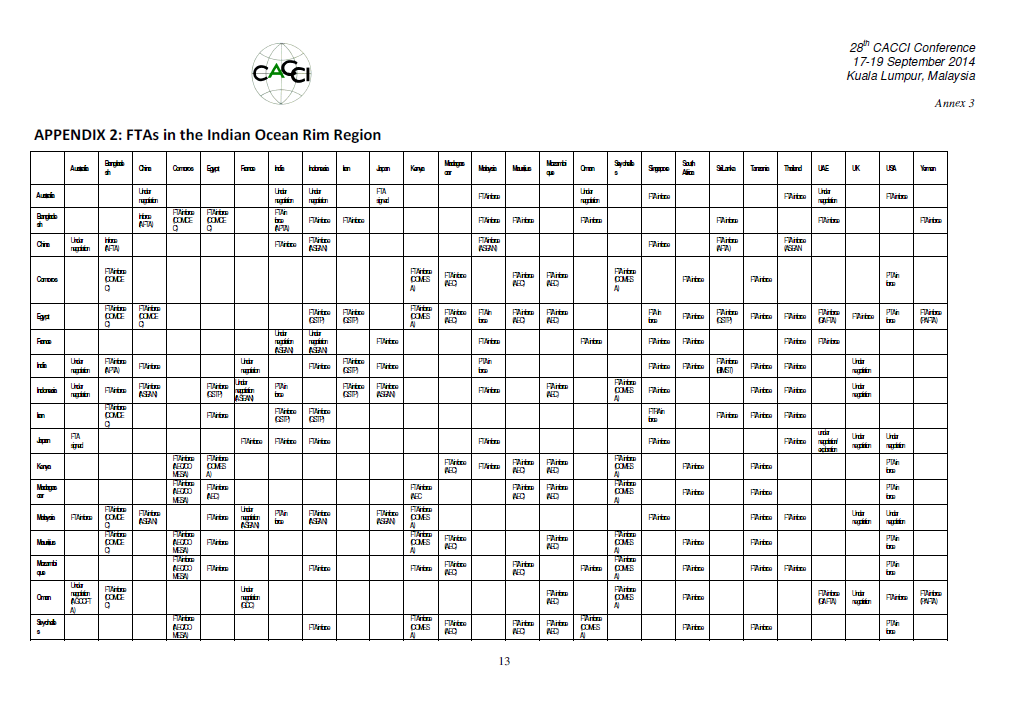

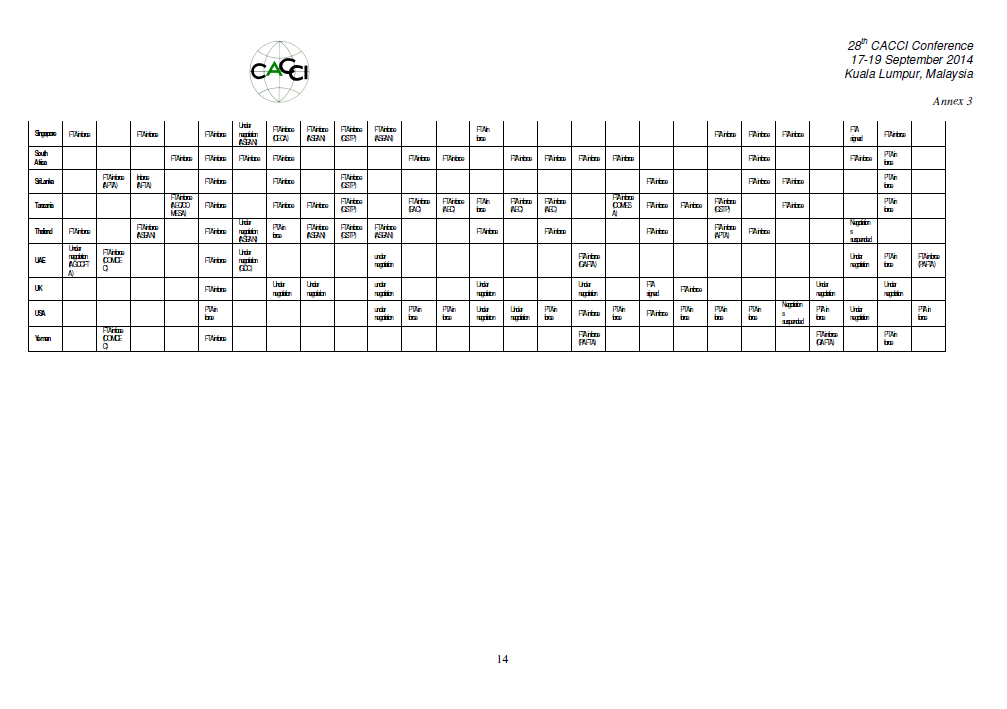

The table above indicates the countries involved (or potentially involved) in regional FTA’s. Further information on bilateral FTAs is included in the Appendices.

Across these agreements, however, there are a range of administrative instruments in terms of both the methods for calculation to determine origin and also the documentary requirements. Companies need to be aware of the differences in order to take advantage of the terms of the agreement and the documentary requirements. The requirement for knowledge and the document handling process adds real costs to business. Streamlining or harmonisation with existing business practice reduces costs for business. Variations across each FTA (exacerbated if the one country has multiple systems in place) increase the transaction costs to the commercial sector under any given FTA.

Similarly we would imagine that Customs costs also rise with variation in schemes, as officials receiving documents need to differentiate between applicable FTA’s as the goods pass through the border.

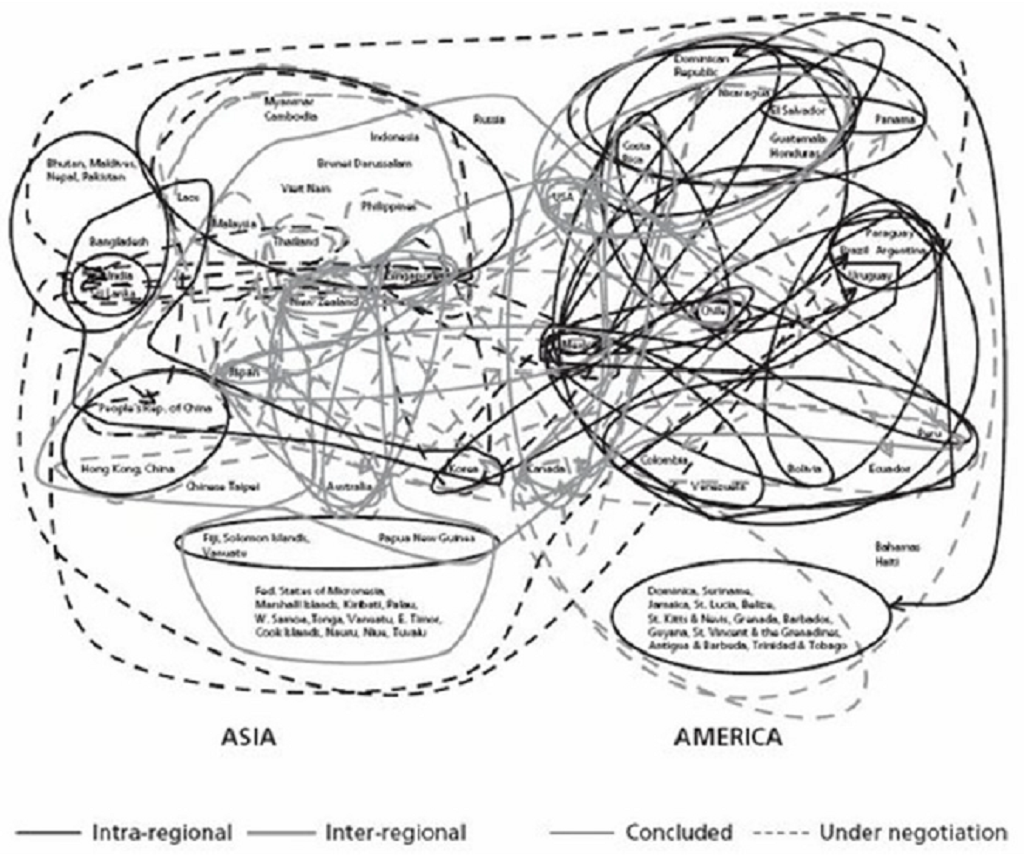

The “spaghetti bowl” of FTA’s in the Americas and Asia-Pacific (2005)6

There is increasing concern globally that the rise of bilateral and regional FTA’s is causing increased complexity, which in turn is reducing the value of the agreements to the commercial sector. Various commentators have coined this the Spaghetti Bowl, or the Noodle Bowl effect. This reflects issues that overlapping and inconsistent rules and administrative requirements result in confusion for international business.

In recognition of this, in 1953 The International Chamber of Commerce submitted a resolution to the Contracting Parties to GATT recommending the adoption of a uniform definition for determining the nationality of manufactured goods. This resolution proposed the concept of last substantial transformation. This proposal, while not adopted by GATT, was influential and was eventually adopted in the 1974 International Convention on the Simplification of Customs Procedures.7

It is also worth noting that at the World Customs Organization two-day conference on rules of origin around the world (Getting to grips with origin, Brussels, 2008) it was reported:

“With regard to preferential rules of origin the Director [Mr. Antoine Manga, Director Trade and Tariff Directorate] of the World Customs Organization emphasized that the growing complexity of various sets of preferential rules of origin could have harmful effects for the international trading system. Customs administrations and the private sector had to cope with a plethora of different rules of origin contained in various trade agreements which sometimes are even overlapping. He reminded the audience of the Conference that the web of incoherent and intricate rules of origin was difficult to administer by Customs administrations and that various sets of rules of origin could also greatly complicate production processes of suppliers which were obliged to tailor their products for different preferential markets in order to satisfy the requirements of specific rules of origin. Therefore, economists spoke about a ‘spaghetti bowl’ phenomenon of rules of origin.”

Currently FTAs do not necessarily incorporate the WTO Bali package, nor the WCO tools on this subject.

CACCI calls for Government to work with industry groups including exporters and importers to better improve the outcomes in trade negotiations, in the interests of co-opting business practice and promoting harmonisation of international trade, rather than making it needlessly complex. CACCI should support establishment of and involvement in local trade facilitation committees as required within the Bali package.

The recent B20 Summit in Sydney recognised that international trade is the world’s growth engine. It is essential to securing global job creation and higher living standards. Trade will be critical to the G20’s objective of raising global growth by at least 2 per cent above business-as-usual targets over the next five years. Therefore, it is concerning that trade growth is still well below pre-global financial crisis levels.

The international business community strongly urges G20 Leaders to stamp their authority on the global trading system by securing trade as a core feature of the G20 Agenda. A targeted set of four high impact B20 recommendations8, if implemented, could generate up to $3.4 trillion in GDP growth and support more than 50 million jobs across the G20 economies. This would be akin to adding another Germany to the global economy. Business therefore encourages each G20 economy to incorporate an ambitious domestic reform agenda, which explicitly targets trade-enhancing measures, into their Country Growth Strategies. This will encourage countries and businesses to allocate their scarce resources to the industries and activities where they are most competitive, acknowledging that ‘Made in the World’ is the reality of modern global trade.

The recommendations cover:

- Rapidly implement and ratify the Bali Agreement on Trade Facilitation

- Reinforce the standstill on protectionism and wind back barriers introduced since the implementation of the standstill, especially non-tariff barriers

- Develop country-specific supply chain strategies

- Ensure preferential trade agreements realise better business outcomes

CACCI endorses the B20’s recommendations on trade and trade facilitation and urges the Governments of members to urgently adopt the protocol on the Trade Facilitation Agreement in the WTO.

With the participation by government as well as private sector representatives from 12 member-states (Australia, Comoros, India, Iran, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Malaysia, Seychelles, South Africa and Tanzania), two dialogue partners (France and the USA), the International Trade Centre (ITC) and the World Bank, the first Business and Trade Facilitation Workshop was held in Mauritius on 4-5th August 2014.

Member States agreed that the World Bank’s Doing Business Index was a good benchmark to measure the propensity of countries to carry out continuous reform in trade and business facilitation. Countries need to emulate the best frontier countries in order to improve their domestic practices.

Since no global consensus could be reached on the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) at the last WTO meeting, participants agreed that the implementation of TFA could nevertheless be implemented by countries unilaterally.

The currently DRAFT Recommendations from the workshop address a range of issues including:

- Pursuing an agenda for IOR region business and trade facilitation at the World Bank by formulating a Business and Trade Facilitation Regional Implementation Plan;

- Establishment of an intra-private sector consensus in the region in order to educate private sector cohorts on policy positions prior to high level negotiations.

- A feasibility study on the business travel card across IOR region,

- Peer-to-peer learning mechanisms on: (i) customs procedures and documentation, (ii) registration of companies, and (iii) emulating the example of the Australian Trade Links as a platform for information sharing.

- Members expressed interest in a Free Trade Area for IORA.

- Effective

- Efficient

- Accepted

- Predictable